Don't lose the plot

On Sinclair Lewis, Homer Simpson, and why the AI gold rush shouldn't make us think that computers are really thinking and living for themselves

Authors create characters every day. They show up in books, movies, plays, television shows, radio series, podcasts, short stories, and games. Many of them are complex, many are entirely believable, and many go on to be incredibly long-lived. We even attribute words to characters, knowing that they really belong to their human authors.

■ Nobody believes that the creation of these characters is the same as creating an actual, conscious new being. Homer Simpson, Juliet Capulet, and Odysseus all seem perceptible as if they were real, but we know that they are not.

■ How characters are treated does tell us a great deal about their authors. If writers seem to love their own characters, that comes through in their stories: Sinclair Lewis cared about his conformist creation, George Babbitt, just as the writers’ room loved the deeply flawed family of Righteous Gemstones.

■ Creators can give their characters terrible flaws and cause terrible things to happen to them while loving them nonetheless, because they aren’t real beings. It would be cruel to force the dramatic plots of fiction -- loss, war, plague, bankruptcy, heartbreak -- on real people just for entertainment, but imposing those problems on created characters is the very essence of dramatic tension. (Creators who make bad things happen to characters to whom they are indifferent tell something else altogether about themselves.)

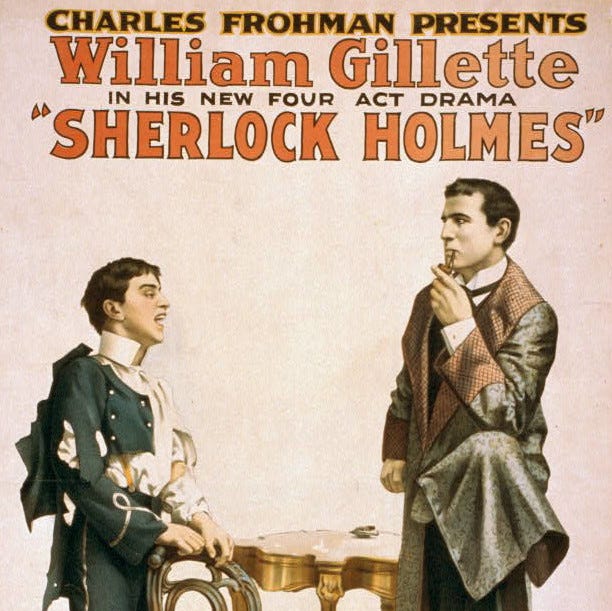

■ We have a fast-closing window of opportunity to anchor our understanding of artificial-intelligence tools in what we know about these fictional characters from the world of entertainment. AI agents and programs are not new beings; they are new characters. How we create and treat them will reveal much about our own humanity, but it doesn’t make them into new souls any more than Arthur Conan Doyle made a real detective by writing tales about Sherlock Holmes.

■ This is a much more contentious claim than it might at first appear. All around there are people creating AI “girlfriends” for money, putting synthesized DJs on the radio, and creating digitally synthesized “actors”. Some are even turning to AI creations for spiritual guidance.

■ No matter how convincingly these tools mimic real beings, we’ve got to remember that they are not. The technology may be new, but the archetype really isn’t.