Fusion ignited

On the first flight at Kitty Hawk, public approval for same-sex marriage, and how we should set our expectations for fusion energy

Not many announcements have initiated the same kind of speculation as the US Department of Energy's announcement that the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory had successfully achieved "fusion ignition" -- "the first controlled fusion experiment in history [that] produced more energy from fusion than the laser energy used to drive it". One physicist thinks fusion power could be as close as 10 years away, while others say fusion power plants are decades off.

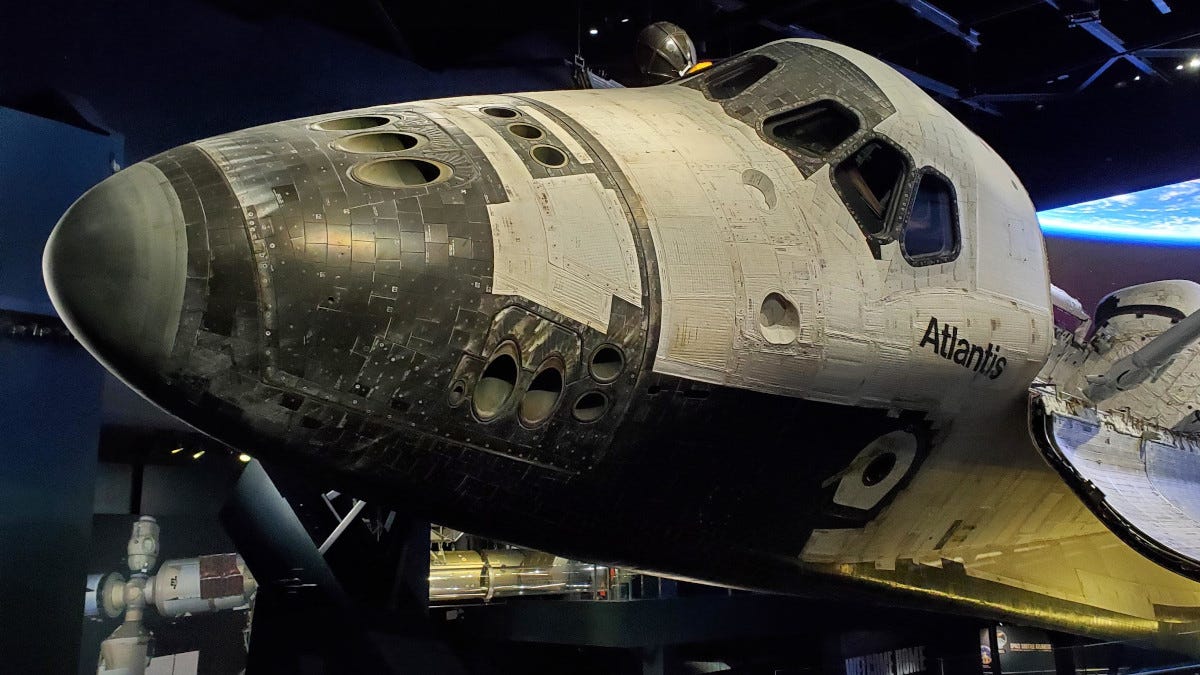

■ There are no straight-line projections when it comes to meaningful change. Whether the subject is human society or technological progress, things tend to change along timelines that have compounding effects. Public approval for same-sex marriage grew very slowly from 1996 until about 2009, then rapidly blasted right through majority approval and charged along to super-majority approval. The last Space Shuttle flew in 2011, fundamentally no different from the first flight in 1981 -- and then, in 2015, rockets started landing vertically.

■ Progress is often both accretive and compounding: Small changes start to add up very slowly, but after a while they start to look like dramatic inevitabilities. And there is never a shortage of self-promoters who will show up and claim that their "disruptive" or "innovative" views of the world are what caused the changes to happen. Certainly, some individuals really are spectacular dynamos -- sometimes, a real Thomas Edison really does come along and change everything.

■ But much more often, the advancements we see in the world look spectacular because the incremental improvements along the way escaped serious notice. For good reason, people are often too optimistic about changes on a five-year horizon, but too pessimistic on a fifteen-year basis.

■ We live in a world often obsessed with celebrity and showmanship, which tends to reward those who aggressively try to steal the spotlight. But even breakthroughs like controlled nuclear fusion stand on the shoulders of decades of accumulated individual contributions.

■ Humans need to be more comfortable with that incrementalism as we are with celebrating apparent breakthrough achievements. And we should also be far-sighted enough to realize that even if the apparent breakthrough doesn't translate into instantaneous improvement, we need to think ahead with policies and social expectations that account for the possibility that we're being too optimistic in the near term, but far too pessimistic in the long run.

■ From Kitty Hawk (1903) to Apollo 11 (1969) was only the span of two human generations, and well within many individuals' lifetimes. Just as things often aren't as bad as they seem but can get worse much faster than we can imagine, it's also generally true that worldly matters are never perfect but are often improving in ways we simply don't accurately detect.