More than a job

On settling down, eulogy virtues, and why everyone ought to let go of their plans just a little bit in early adulthood

Sometimes it must be assumed that people share absurd opinions on social media for the express purpose of generating engagement via click-rage. Little else could explain just shockingly bad advice like one person's advice: "Don't fall in love from 22-29, there's to[o] much to lose. Your career will thank you."

■ Far better advice would be, "Don't become monomaniacal from 22-29; there's too much to lose." A single-minded obsession with one's career at that age is terrible advice on a human level, generally: Nobody ever knows when they might be struck down by injury or illness far before their prime, and to have squandered one's twenties on career alone could turn out to be a grave error.

■ But even as career advice, "Focus exclusively on your job" is a terrible recommendation. A person may certainly take pains to control when or whether they choose to escalate from "falling in love" to "raising a family"; that's perfectly fine. But love is an entirely healthy and reasonable part of a well-rounded life. So are friendships. And so are the non-occupational pursuits that put us into positions that expose us to opportunities to find friends or fall in love.

■ A person who doesn't afford themselves the opportunity to do those other things -- by joining a recreational bowling league, or volunteering at a hospital, or worshipping with a faith community, or having meals with others -- is guilty of cutting themselves off from the prospect of a well-integrated life. Hobbies and club memberships and travel all serve to make a person's life experience not only more extensive, but more whole.

■ That wholeness is important, first and foremost, as a part of one's biography. In the words of Ben Sasse, "Many of us might be unintentionally displacing lifelong 'eulogy virtues' in favor of mere 'resume virtues.'" But that integration of one's life inside and outside of work is also important in the strictly occupational sense, too: Experiences in lower-stakes environments give people practice in how they will respond to challenges in higher-stakes environments.

■ The person who shirks their duties at the Rotary Club or who cheats on a golf game may well be the type most others would want to avoid in business, too. But the person who can lift a little more than their share of the load or who can welcome a newcomer in environments where there's no supervisor watching is the kind of person who gets practice in the essential soft skills that matter so much elsewhere -- especially in an economy where services outweigh goods two-to-one. How we engage with other people matters a great deal. To think "your career will thank you" for behaving otherwise is delusional.

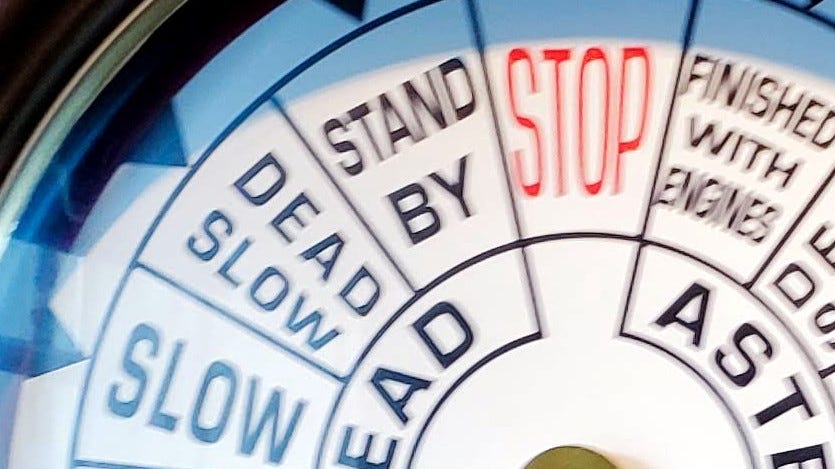

Full speed ahead isn’t always the right answer