Puzzles and the future of AI

On protein folding, problem solving, and the way computers could help humans figure out problems more humanely

Countless breathless commentators have opined about either the unlimited potential or the unspeakable dangers of artificial intelligence. So far, the evidence is entirely mixed: Some examples of AI, like using machine learning to assist in complex scientific problems like protein folding, weigh on the good side of the scale. Others, like some of the bizarre hallucinations served up as authentic search results, weigh heavily on the bad.

■ As with all technologies, the extent to which AI is good or bad depends upon the values of the people using it. And it's being used badly by many, to be sure -- the evidence points to widespread abuse by people submitting partially or completely AI-generated, nonsense-stuffed papers to academic journals, just for example. But there is a wide scope of possibility for it to be used well, particularly if it's put to use as an aid to human thinking (rather than as a substitute for it).

■ Human minds are wired to try to solve puzzles. It's why we see shapes in the clouds and form superstitions -- our brains are very good at making connections, even when they are not justified. Artificial intelligence tools could be put to extremely good use in breaking complex problems into human-friendly pieces.

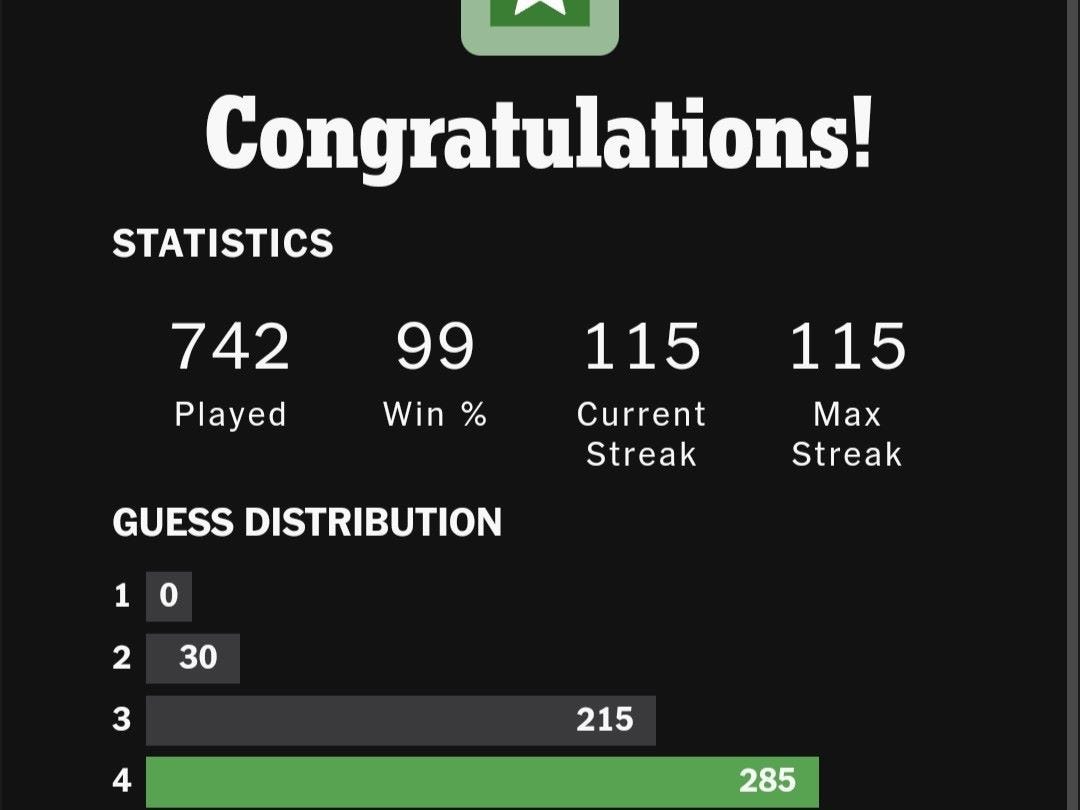

■ Small puzzles are attractive -- millions of people play Sudoku or Wordle or Jumble or the New York Times Crossword. It's when problems seem too big or lack obvious constituent parts that people shy away.

■ That's where AI should be asked to step in. It's probably not ready yet, either in terms of sophistication or data and human safety. Lots of problems are complicated specifically because there is no existing path to a solution, and others bear heavily enough on personal choices that we need to be wary of turning over too much intimate detail to systems with insufficient safeguards.

■ But AI is likely not too far removed from the stage when it could analyze large problems and recommend bite-sized component pieces -- puzzles, really -- that could appeal to our natural instincts. These puzzles could make work seem more interesting and big personal questions seem less daunting. That would be a highly human-centered way to put high technology to use.