Righting educational wrongs

On football, political drama, and the long project to advance educational access

Education is all too often treated as an object -- a thing to be possessed, much like a football on a field. Someone holds on to it and moves it in their preferred direction for a while, then someone else takes it in another direction. The contest over the object sooner or later overwhelms the meaning and purpose of education itself.

■ Great forces, from unions to parent groups and from mega-donors to the Federal government, battle over who may deliver it, set the rules about it, or decide how much it will cost. The debates get pretty fierce.

■ Indigenous Peoples’ Day serves up a healthy reminder that the intrinsic value of something like education shouldn’t be measured by those battling to control it like some abstract battlefield, but instead by just how hard people will work to get it when they have been denied.

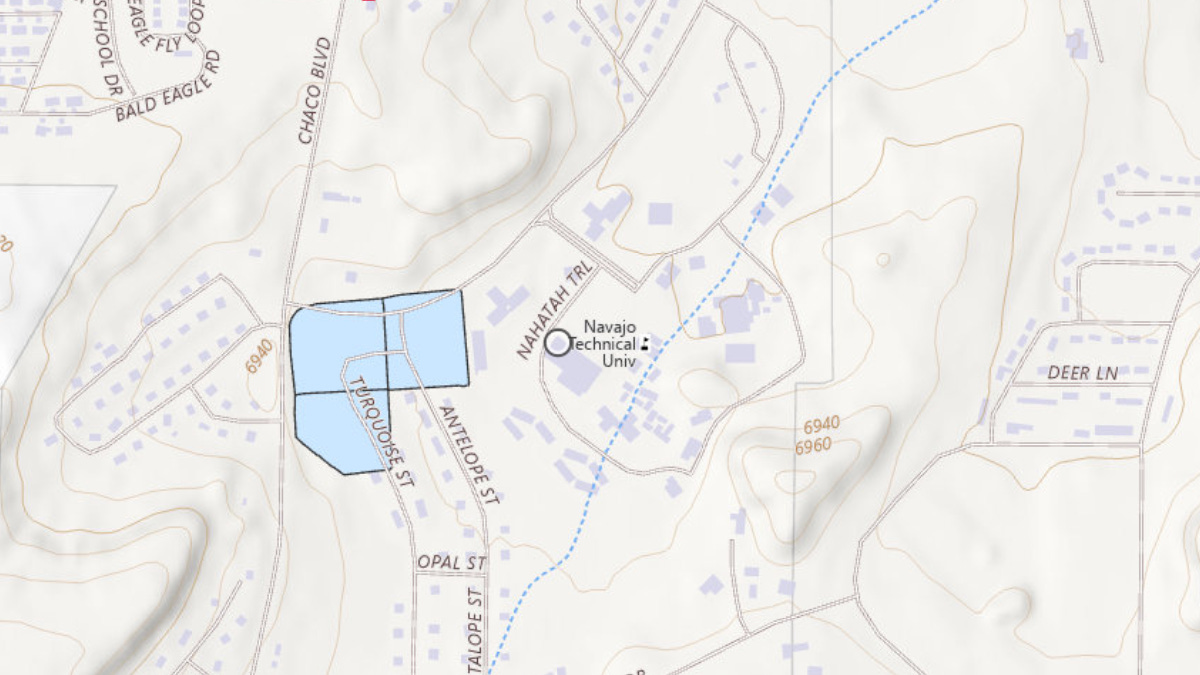

■ The ongoing struggle to correct generational lapses in access to education remains an expensive indignity to overcome. Some 22,000 students are now enrolled in 34 different tribal colleges and universities. That’s a lot of individuals, but bachelor’s degree attainment among American Indians is still half that of the national average.

■ The first tribal college is only 57 years old, which offers some sense about how relatively young the process of correcting past errors still remains. They aren’t the only option, but when it comes to optimizing access and opportunity for people who have been overlooked or left out for generations, colleges close to enrolled tribal members are an important solution. Not everyone needs a degree, of course, but if communities are chronically left out of the degree pipeline, it’s bound to be economically costly for them.

■ Seen this way, education doesn’t look much like a football to fight over. It looks more like a valuable good that becomes even more valuable the further it is spread, whether through scholarships or other support.