When bad things don't happen

On shots delivered, forecasts that get it right, and the cultural value of good professional conduct (and appropriate public deference)

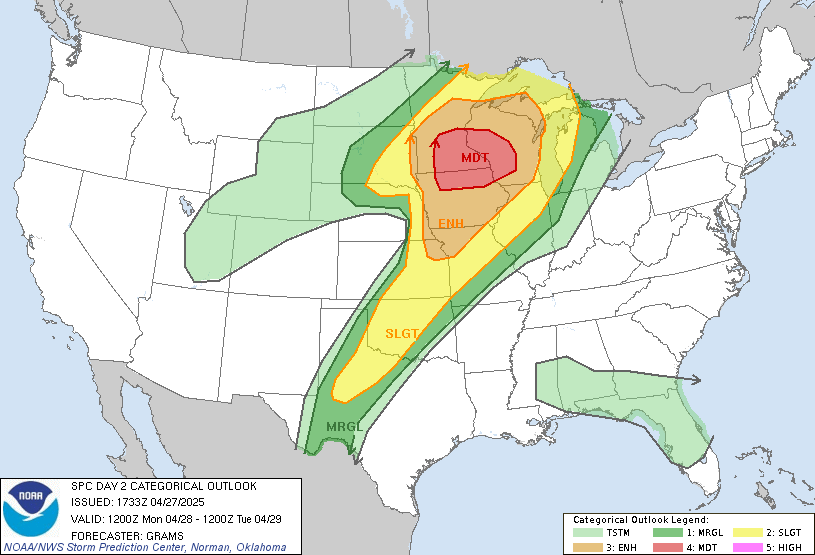

The Storm Prediction Service, one of many enormously valuable components of NOAA, has sounded the alarm in a most serious way about the prospect of a dangerous tornado outbreak that could materialize in the Midwest on April 28th. Their forecasts have been flagging the event for days, and local meteorologists have been amplifying the message despite idiotic and occasionally nasty public feedback.

■ Something dramatic is quite likely to occur, but some people in the alerted regions will experience it and others won't. Then the painfully predictable complaints will ensue: "Why did you get us so worked up about this thing that didn't happen [to me, even though it still happened near me]?"

■ A cultural value we have plainly done not enough to cultivate is an appreciation for the bad things that don't happen. Modern, advanced civilization does a great deal to shield us from horrors that were utterly commonplace in days gone by. There was a time, not long ago, when tornado forecasts were practically unheard-of, and even warnings of verifiable events happening in real time were haphazard and poorly disseminated.

■ It's not just the case with weather, either: Go back to 1850, and well over 20% of deaths in the US were attributable to contaminated drinking water, a problem given next to no public thought today. We fixed the problem, and now bad things don't happen -- but nobody's counting. Likewise, routine childhood vaccinations have likely saved more than a million young lives in the last 30 years -- but it's hard to give anyone credit for the bad thing that didn't happen.

■ This is a cultural problem worthy of some attention, because some people are insistent on touching the hot stove. In our midst, we have vaccine fabulists, "raw water" advocates, and jerks profiting off fictitious weather forecasts on social media. All of them undermine work being done by responsible professionals.

■ There isn't enough time in the world to explain to everyone why every safety practice or prevention step has emerged over time. Even if time weren't a factor, audiences rarely have the patience to listen -- and the least patient are the ones who need to hear those messages the most.

■ It's truly a matter of establishing and enforcing cultural norms around professionalism: Good professions must police themselves scrupulously, and the rest of us amateurs need to heed what they tell us. Their successes will often take the form of bad things that don't happen (to wit: people not dying of vaccine-preventable diseases, of waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid, or of injuries from surprise storms) -- but the last thing we should do is assume that those disasters avoided don't count for something good.